Exit codes, also known as return codes or exit statuses, are numerical signals that a program, command, or script sends back to the operating system (or calling process) when it finishes running. You don’t need to dig through potentially lengthy log files to diagnose a failure – an exit code often provides a quick clue about the nature of the problem.

The universally accepted convention is that when a program runs successfully, it returns an exit code of 0. Any other number, typically within the standard range of 1 to 255, indicates that something went wrong.

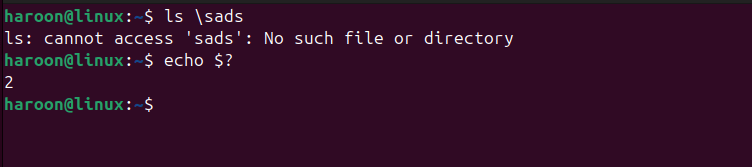

The simplest way to check the exit code of the last executed foreground command in Unix-like shells (such as Bash or Zsh) is by inspecting the special shell variable $?. For example, first run any command and then check its exit code:

ls /nonexistent_directory

echo $?

The echo $? command displays the numerical exit code stored in the $? variable. If you see 0, it means the previous command completed successfully. A non-zero value like 1, 2, or 127 indicates an error, and the specific number offers a clue about the type of issue — perhaps a missing file, a nonexistent directory, or insufficient permissions.

Debugging Your Script With Exit Codes

Exit codes are especially useful when you’re writing shell scripts. They help your script determine whether something went right or wrong, allowing it to decide what to do next.

Here’s a simple example that copies a file to a backup folder and reports whether the copy was successful:

#!/bin/bash

# Try to copy the file

cp important_file.txt backup/

# Check if the copy was successful using the exit code ($? holds the exit code from the last command)

if [ $? -eq 0 ]; then

echo "Backup successful!"

else

echo "Backup failed with exit code $?"

exit 1 # Exit the script with an error code to indicate something went wrong.

fiWhen the cp command runs, it returns an exit code. An exit code of 0 means everything went smoothly. If the code is not 0, something went wrong – and the script prints an error message and exits with a code of 1.

Setting Your Own Exit Codes

In addition to checking the exit codes from commands, you can define your own exit codes to indicate different types of errors. This practice makes your scripts more informative, allowing anyone using them to understand exactly what kind of problem occurred.

Consider this script:

#!/bin/bash

# Verify that an argument (filename) is provided.

if [ -z "$1" ]; then

echo "Usage: $0 <filename>"

exit 1 # Exit code 1 indicates that no argument was provided.

fi

# Check if the file provided as the first argument exists.

if [ ! -f "$1" ]; then

echo "Error: File not found"

exit 2 # Custom exit code 2 indicates that the file was not found.

fiIf someone runs your script, and it fails, they can refer to the exit code to determine the exact error. In this example, exit code 1 signals that the user did not provide a required argument, while exit code 2 explicitly indicates that the file wasn’t found. This structured approach is especially useful when your script is part of a larger system or when another script depends on its output.

List of Common Exit Codes

While different programs can define their own exit codes, there are some common patterns you’ll see across many command-line tools – especially in Linux and Unix-like systems. Here are some of the most frequently encountered:

- 0: Everything’s good! The program ran without any problems.

- 1: Something went wrong, but the error isn’t specific. This is like the catch-all of exit codes.

- 2: Misuse of shell builtins. This can occur if you use a command incorrectly, such as forgetting required parameters.

- 126: The command exists, but you don’t have permission to run it.

- 127: Command not found. This means the command doesn’t exist or isn’t in the system’s path. Double-check your spelling.

- 128: Invalid exit argument. You’ve used a number that doesn’t make sense as an exit code.

- 130: Program terminated by Ctrl + C. This happens when you manually stop a program.

- 137: Out-of-memory (OOM) condition.

- 255: The program tried to return an exit code outside the valid range.

Some specific programs have their own unique exit codes. For example, grep returns 0 when it finds matches, 1 when it doesn’t find any matches, and 2 when there’s an error. Also, developers can technically use almost any number (usually 0 to 255 on Unix-like systems).

Chaining Commands Based on Success or Failure

Bash also provides two handy operators && and || that let you string commands together depending on whether the previous one succeeded or failed:

- && (AND operator): Runs the next command only if the previous one succeeded (exit code 0).

- || (OR operator): Runs the next command only if the previous one failed (non-zero exit code).

For example, suppose you want to create a directory and then immediately change into it. If creating the directory fails or changing into it doesn’t work, you might want to display an error message:

mkdir new_directory && cd new_directory || echo "Failed to create and access directory"Here, mkdir new_directory tries to create the folder. If that works, the code immediately runs cd new_directory. If either step fails, the || operator kicks in and prints the error message.

Final Thoughts

Exit codes might seem like a small detail, but they’re part of what makes command-line tools so powerful. They create a common language for programs to communicate about success and failure, which is essential for building complex systems.

If you’re new to command-line work, start by getting in the habit of checking echo $? when commands don’t behave as expected. Soon, you’ll be using exit codes in your own scripts and appreciating this simple but effective communication system.